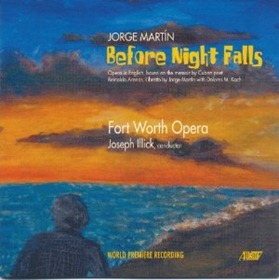

JORGE MARTÍN (1959 – ): Before Night Falls – W. Mason (Reinaldo Arenas), S. Mease Carico (Victor), J. Garcia (Ovidio), J. Hall (Mother, the Sea), C. Ross (the Moon), J. Blalock (Lázaro), J. Abreu (Pepe), C. Trahan (Port Official, Visa Official); Fort Worth Opera Chorus, Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra; Joseph Illick [recorded in Fort Worth, TX, during Spring 2010; Albany Records TROY 1226/27]

There are in virtually every age of humanity those individuals and situations that capture the popular imagination, whether within the limited scope of specific places or on a global scale. Through oral traditions and, eventually, the endeavors of artists, these figures of collective importance are subjected to a kind of etherized immortality in which they are indefinitely preserved but are not unchanging: as the years pass, there are many cases in which the ideals for which a person is remembered become more important in the context of mythological consciousness than the facts that contributed to the legend. There was, for instance, Cleopatra VII Philapator, the Greek queen who was Egypt’s last fully legitimate Pharaoh regnant, a woman who during her life wielded as much power and influence as did any woman on earth. Within a century of her death, however, she was rather than an exceptional woman a figure in fanciful histories, a character in the drama that was Rome in the years before its collapse. To a generation of American opera-lovers, Cleopatra was Beverly Sills, her Hellenic authority taking the form of brilliant displays of coloratura and interpolated top notes that shone like the summer sun on the surface of the Nile. For lovers of cinema, Cleopatra was Elizabeth Taylor, a beguiling seductress whose lavender eyes could bend the will of Rome. Before either Georg Friedrich Händel or Joseph L. Mankiewicz adapted Cleopatra to their artistic ends, William Shakespeare had endowed his Antony and Cleopatra with a female heroine so monumental as to seem almost caricatured and scornful but whose suicide was depicted with extraordinary tragic grandeur, an Elizabethan Liedestod. Though undoubtedly an exceptionally cunning and educated woman to whom Homer would have been as familiar as to the greatest scholars of the European Renaissance, Cleopatra VII Philapator was almost certainly neither the graceful consort nor the timeless beauty artistic depictions of her have introduced into pseudo-historical perceptions. The extent to which these well-intended artistic prevarications have affected the cultural legacy of Cuban dissident poet Reinaldo Arenas, the subject of Cuban-born composer Jorge Martín’s opera Before Night Falls (taken from the English title of Arenas’s posthumously-published 1992 autobiography Antes que anochezca) whose life has already been explored in a film with the same title that featured an Academy Award-nominated performance by Spanish actor Javier Bardem, is perhaps more difficult to ascertain than with a figure from the distant past like Cleopatra. The best sources of information about Arenas, who took his own life in 1990 after a draining battle with AIDS, are his own writings, many of which are at least allegorically autobiographical and decry the atrocities of Fidel Casto’s Cuba. The libretto of Before Night Falls, the work of the composer and Dolores M. Koch, is commendably faithful to Arenas’s own writings. Determining whether the Reinaldo Arenas we meet in Mr. Martín’s opera is the man as he actually was can only be left to history, but what the poet’s writings and the opera establish is that Arenas was one of those men whose life, whatever the gilding of legend will make of it, was both of his own time and for all time.

Mr. Martín’s and Ms. Koch’s libretto must be commended at the start for never getting mired in the post-Revolution politics of Cuba in the Twentieth Century. This is an opera built upon the foundation of a compelling central figure rather than an abstract political manifesto. Politics lurks in every dark corner of the drama, of course, but the listener’s attention is focused on the impact of the political machinations faced by Arenas and the other characters in the opera. Equally essential to the psychological construction of the opera is the issue of Arenas’s homosexuality, something that was especially dangerous in his native Cuba and remained contentious even in the United States during the final years of his life. Mr. Martín as both composer and librettist, along with Ms. Koch, is to be praised for approaching the subject of Reinaldo Arenas with a sensitivity and honesty that elude many directors of recent productions of operas such as Billy Budd and Peter Grimes, in which characters’ implicit or presumed homosexuality has been artificially given greater importance than their humanity. It is of considerable significance to his legacy that Arenas was a gay man, and as an aspect of his cultural genesis this story should and must be told. As with the untold numbers of gay artists who were tortured and killed by the Holocausts wrought by Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russian, though, what is most important, indeed most poetic, about Arenas is that he was, all else aside, a man, equally remarkable and unremarkable. The lasting meaning of Arenas’ plight as an artist is in his humanity, not his sexuality, and the valiance with which he bore his own persecution and the exasperating sorrow with which he witnessed the suffering of his fellow men. Arenas would likely have agreed that his sexuality was an element of his life rather than its impetus, and Mr. Martín integrates Arenas’s sexuality into the opera in a manner that, without politicizing any aspect of the drama for the sake of sermonizing, honors the sense of love as an abiding necessity in the life of any man, regardless of his sexuality. Before Night Falls is not a social treatise in operatic form charged with altering perceptions: operating within the parameters of traditional forms, Mr. Martín’s opera examines Arenas’s struggles as those of one man united with Everyman, like Rigoletto’s, Wotan’s, or Boris Godunov’s. The libretto of Before Night Falls is, like Arenas’s own writings, colloquial and unfailingly eloquent. One hears the voice of a beautiful, tormented man in words that he might have written himself.

Musically, Mr. Martín’s score is tonal without ever seeming dated and makes clever, understated use of many rhythms native to Reinaldo Arenas’s Cuba. Rey’s first extended solo is sung over an engaging habanera, and even contemplative passages benefit from thoughtful rhythmic underpinning. Unlike many of the operas written during the first decade of the Twenty-First Century, Before Night Falls is unquestionably an opera after the models of history, its tonal palette expansive and far removed from contemporary musical theatre. It is audibly an opera of its time but none the worse for that. There are, in fact, many passages of great beauty in the score, not least in the first-act trio for Ovidio, Rey, and Pepe, ‘Oh, our unhappy island,’ and the Epilogue, Rey’s death scene. There is often an almost Mozartean grace in the ensemble writing, and Mr. Martín shares with Benjamin Britten the skill for making male voices, even when dominant within the aural landscape, individual and sharply characterized. The composer largely leaves musical evocations of Cuba in the orchestra, contrasting the often-complex dance rhythms with vocal lines that are both melodically appealing and conducive to pointed delivery of the text. Successful both musically and dramatically, Before Night Falls is among the sadly few genuine operas composed during the first decade of the new millennium that not only deserved a studio recording of its premiere production but also deserves a place in the repertories of the world’s important opera houses.

That premiere production, the result of espousal of the opera by Fort Worth Opera General Director Darren K. Woods, led to a recording that, as a document of the creation of an important opera by a cast of committed, talented young artists, is superb. Produced for Albany Records by John Ostendorf, himself one of America’s finest singers and a veteran of many excellent recordings, the recording has excellent sound quality that preserves theatrical ambiance without sacrificing tonal or verbal clarity to reverberation. The effect is similar to being in the first tier of an acoustically bright house, with the balance among orchestra, chorus, and soloists ideally achieved. Mr. Martín employs the chorus almost as they would be used in a Greek tragedy: the chorus of Rey’s embittered Aunts, though tonally distant, is not unlike choruses of Furies in the operas of Gluck. Whether as these complaining crones, as jubilant revolutionaries, or as oppressed prisoners, the Fort Worth Opera choristers, thirty-one in number, sing very well throughout the performance. Likewise, the Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra play with precision and verve. Presiding over the performance is conductor Joseph Illick, Fort Worth Opera’s Music Director. Conducting with the zeal of advocacy that never gets in the way of the kind of straightforward music-making that lends a genuine sense of occasion to the performance, Maestro Illick brings extensive experience in mainstream repertory to his pacing of Mr. Martín’s opera. Maestro Illick is the sort of conductor whose quiet mastery of operatic timing and the difficult balance between stage and pit is so welcome in America’s regional opera houses and, with only a few notable exceptions, so conspicuously absent in America’s larger houses. It is evident in every note on this recording that Maestro Illick, Mr. Woods, and the Fort Worth Opera forces were as committed to Mr. Martín’s opera as the composer was to honestly and touchingly portraying his subject.

In the opera’s female roles, sopranos Janice Hall as Rey’s mother and the Sea and Courtney Ross as the Moon bring firm, lovely voices to their music. Ms. Hall is especially moving in the aria for Rey’s mother, ‘Promise me, child.’ Mr. Martín’s music for the Sea and the Moon, symbolic figures who essentially serve as Rey’s muses, is often ethereally beautiful, reminiscent in spirit of Richard Strauss’s music for the nymphs in Ariadne auf Naxos. The lullaby sung by the Sea and the Moon in the final moments of the opera, following Rey’s death, also conjures the Strauss of the final trio of Der Rosenkavalier and the final scene of Capriccio. As the Port and Visa officials, Corey Trahan discloses a lovely, light tenor voice of the type that, since the heady days of Hugues Cuénod and Michel Sénéchal, has become steadily rarer.

A quartet of gifted young singers take the roles of the four men whose lives intersect most meaningfully with Rey’s in the opera. As Victor, a commandant in the revolutionary force that ousted Fulgencio Batista and swept Fidel Castro into power in Cuba, bass-baritone Seth Mease Carico sings with the dark authority required to convey in vocal terms alone the oppression imposed upon Rey and other Cuban dissidents. Mr. Carico is especially commanding and powerful in the Interrogation Scene that occurs after Rey has been imprisoned at the infamous Castillo el Morro, a scene that in its dramatic effectiveness and emotional impact brings to mind the scene for the title heroine and the Zia Principessa in Puccini’s Suor Angelica, as well as the tense Interrogation Scene with piano accompaniment for Giordano’s Fedora and Ipanov. Vocally and dramatically, Mr. Carico’s Victor is rather like a young, very dangerous Scarpia.

Rey’s deliverance unto Victor and the revolutionary forces is accomplished when he is betrayed by Pepe, his childhood friend. Sung by Puerto Rican tenor Javier Abreu, Pepe emerges as a conflicted figure whose denunciation of Rey is an act of self-preservation rather than one of direct malevolence. Mr. Abreu possesses a lovely lyric tenor voice that brings a suggestion of sadness to even his most exuberant lines and blends beautifully with the voices of his colleagues in ensembles. Though Pepe’s actions set in motion the horrors that pursue Rey during his last years in Cuba, Mr. Martín’s music portrays Pepe in a largely sympathetic way, and Mr. Abreu’s vocal elegance shapes a Pepe who is a decent but scared young man.

Mr. Martín and Ms. Koch elected to create a composite character to serve as Rey’s poetic mentor, a figure whose role draws upon the qualities of several important artistic influences in Arenas’s life. This role, Ovidio, is sung by tenor Jesus Garcia, whose performances as Rodolfo in Baz Luhrmann’s Broadway production of La Bohème were widely acclaimed. Mr. Garcia brings to Ovidio, a role that in its determined and stern but benevolent philosophizing is not unlike Seneca in Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea, a voice that is both youthful and suggestive of experience: there is the resignation of knowledge and understanding in his singing, a quality reinforced by Mr. Garcia’s world-weary inflection of the text. The vigor of Mr. Garcia’s singing makes an apt impression in his role, the burnished tone with which he sings his lines suggesting the very essence of poetry.

Rey’s companion during his final years in New York is Lázaro, a man whom he befriended before his successful escape from Castro’s Cuba. It is to Lázaro that Rey makes the shattering revelation that he has been diagnosed with AIDS, and it is Lázaro who cares for Rey during his illness. Compared with the other characters in Rey’s life, Lázaro is a simpler man, his motives clearer and more emotional than cerebral. As sung by young tenor Jonathan Blalock, however, Lázaro is as central to Rey’s development and ultimate transfiguration as an artist as any of the other influences in his life. The tenderness with which Mr. Blalock sings in his scenes with Rey is immensely moving, as is the despair that floods his voice in the final scene, when his final statements of ‘Farewell’ as he is seen casting Rey’s ashes into the sea have the impact of Rodolfo’s singing of the dead Mimì’s name in the final moments of La Bohème. Mr. Martín infuses Lázaro’s role with music of lyrical grace, and the ardent beauty of Mr. Blalock’s singing gives his performance an abiding authenticity. With excellent diction and a voice that shimmers with a bright patina, Mr. Blalock’s performance as Lázaro gives Before Night Falls and its depiction of Rey’s isolation and decline what is finally needed for the opera to truly work: the profound expression of love, even when it is unspoken, that is required as the impetus of genuine tragedy.

In order to bring the troubled, terrific man at the center of this work to life, a singer of great charisma is required, and the premiere production was fortunate to have engaged Wes Mason, one of America’s most promising young baritones. From his first note, Mr. Mason simply becomes Rey, enveloping himself in the role in a way that is refreshingly uncomplicated. This is not a trick of method acting applied to singing: for two hours, Mr. Mason uses his voice to communicate Rey’s thoughts and words as though Reinaldo Arenas were taking the stage himself. This Mr. Mason achieves not with histrionics or suspect melodramatic devices but with open-hearted, open-throated singing. Mr. Mason’s is a powerful voice, the focused tone and vibrato sounding destined for leading roles in large houses, but this singer is also capable of disarming intimacy without seeming precious. Vocally, Rey’s music is especially demanding in what is, overall, an arduous score, and Mr. Mason not only copes but excels. In his exchanges with his colleagues, and particularly with Mr. Blalock, Mr. Mason is alert to the nuances of his own text and to the changing moods of the opera in general. Mr. Mason possesses the vocal charisma necessary to impersonate Mr. Martín’s Rey, and he recreates in sound the poetry that Arenas constructed of words.

It is likely that, had he contemplated an opera about his life premiering twenty years after his death, Reinaldo Arenas would have been surprised that this musical legacy would greet a world in which Cuba remains under the fists of Castro and in which a man’s sexual preference and manner of exiting this life are still controversial. Though he is sixteen years Arenas’s junior, perhaps Jorge Martín also would not have envisioned this in 1990, five years before he acquired the rights to set Arenas’s memoirs musically. What Mr. Martín accomplishes in Before Night Falls is a sterling example of the fact that, no matter how horrific, debilitating, and unscrupulous the human and inhuman obstacles a man faces are, it is the dignity of the man as he faces them that are of permanent value. It is human nature that a man who dies bravely is remembered whilst a man who lives weakly is forgotten, and there is no doubt that Reinaldo Arenas lived courageously, loved extravagantly, and died resolvedly. All of this is evident in Mr. Martín’s score, in which the ugliness of oppression, pain, and terminal illness is omnipresent, but as an environment in which life goes on until it simply cannot go on any longer. Mr. Martín has composed a wonderful opera that never preaches or wallows: it merely sings of what there is to be sung about a man who, like Tosca, suffered for art and for love. It also reminds the listener of how rare this is, to focus even in art on the integrity of a man’s life rather than the choices he made in living it. It is too soon to hypothesize about whether future generations will remember Javier Bardem or Wes Mason as Reinaldo Arenas rather than remembering the man himself, but it is to the credit of Jorge Martín, Dolores M. Koch, Wes Mason, Jonathan Blalock, Joseph Illick, Darren K. Woods, and all who were involved with the creation and recording of this opera that Before Night Falls is an experience that will not soon be forgotten.